Stefan Goldmann on why Web 2.0 can work for you but won’t for most, where all the money went and how working against the market consensus can be a winning strategy.

Electronic music. What we believed for a long time was that anyone with a bit of talent had a chance at a career of about ten years before eventually retiring from the circuit. Of course there are exceptions for whom this does not seem to apply. Francois Kevorkian has probably had the longest career here (unless we count Kraftwerk as part of our little world); and it’s hard to imagine techno or house without Richie Hawtin, Jeff Mills or Laurent Garnier. That’s the good news: it does not necessarily have to meet a predetermined end. On the other hand, artists emerging now face the hardest times ever to establish themselves. The lifespan between breaking through and being laid off seems to have reached a historic low point of half a year. The reasons behind this “haircut” to artistic longevity are the radically lowered barriers to participation, as well as the hectic marketplace discovering today’s new talent and abandoning yesterday’s new talent.

Let’s clarify “barriers”: in the old days of the music business, which was basically before the end of the 1970s, the main barriers to “making it in music” were studio time and access to distribution. Whoever wanted to be heard adequately needed well distributed releases. That is, having recorded material in the first place. The means for producing such recordings were so expensive that at some point only big corporations could spare the funds to pay for the required studio time and personnel. The effect of this economic barrier to resources was that a couple of hundred artists and bands gained access to an audience of millions. Once a recording was produced it enjoyed a long life in the market due to the lack of competition that otherwise would have pushed it off the store shelves. Only under these conditions did the huge, continuous investments in promotion and distribution actually make economic sense in those times and circumstances.

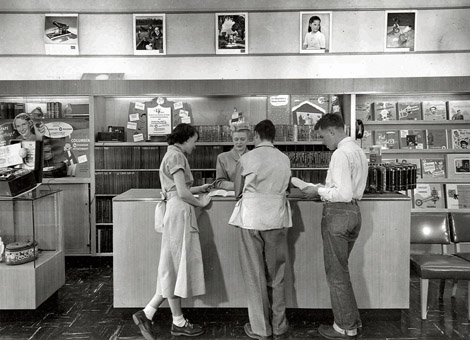

What a typical recording studio once looked like

This model experienced a serious challenge with the advent of the affordable 4-track recorder, which enabled home recording that could deliver marketable results for the first time ever. For instance, the whole late ’70s/early ’80s New York downtown scene can be pretty much explained by this piece of technology. Progress in affordable music equipment in the form of synthesizers, drum machines, these earphones for $50 and samplers gave birth to a plethora of innovative styles in music, including hip hop, house, techno and drum ‘n’ bass. At the same time independent distribution was born, conquering channels previously serviced exclusively by major corporations. The new distributors were capable of connecting with ever smaller target groups. Fueled by enthusiasm, small businesses could survive on small quantities of product previously considered not to be worth the effort. Tango from Finland and death metal from anywhere found comfortable niches with worldwide followings.

These enabled artists and the people around them to become professionals, i.e. to make a living on the music instead of funding a hobby through an undesirable day job. That was the core economic feature of the independent music culture: no riches, but still sufficient funds to avoid wasting time on activities not related to music. Anyone busy generating income from 9 to 5 wouldn’t be able to gain the deep skills necessary to sustain a career in music and hold an audience for long. By the way, this comfortable indie-constellation was never really threatened by the majors, who only occasionally dropped by to sign away the most successful artists of any niche. Working within your own artistic preferences became a pretty comfortable thing to do back in the ’80s.

Closer to what today’s typical studio looks like. Richie Hawtin’s bedroom studio.

The next level was reached when it took nothing but a standard PC and a microphone (if required) to render an entire production. The software that emulated the previously needed pieces of gear came mostly for free thanks to piracy. Therefore, production costs practically hit zero and the record sales you needed in order to sustain a release fell almost to the cost of the manufacturing of the records themselves (with a few bucks for promotion). At that point, at least in dance music, sales figures of just around 5,000 physical units were considered a “hit,” whereas a bit earlier it would’ve required a few hundred thousand units. Many soon realized that even the expense of pressing up records or CDs was not really necessary. A digital download has no costs at all. The logical outcome was distribution that granted any piece of music total availability, with the downside of being the most inefficient way of distribution ever: what should I download when there are five billion files to choose from? Whom should I bless with my attention? Do I have any attention to spare?

Contrary to public perception, this didn’t affect the majors all that much. Their problems were mostly in their inability to maximize the advantages they already had instead of wasting resources on trying to revive an overthrown order. Soon enough it dawned on them that big artists (i.e. those with the biggest turnover) can generate reasonable income through so called 360-degree-deals, covering live gigs, publishing rights, merchandise, etc. all under the control of one company. Even the smallest labels engage in a similar policy nowadays. But the required resources to participate in the game of filling stadiums, really cashing in on movie and advertising deals today are almost exclusively in the hands of majors. Interestingly, the so called “democratization” of music production and distribution didn’t change this allocation of relevant income to the majors’ detriment at all.

For independent artists and small labels, the shift to digital formats presented both freedom and a challenge. On one hand, it allowed them to reach global audiences without traditional distribution costs, opening up new revenue streams without needing to compete in physical markets. However, as competition intensified with millions of tracks available online, artists had to find creative ways to stand out and manage expenses. Much like with other consumer products, savvy listeners and artists alike began exploring ways to save money—whether that was finding discounts on music software or searching for cheaper options for essentials, like ways to save money buying generic Cialis online, a need that parallels artists’ search for accessible production resources. Artists today often juggle music creation with the task of self-promotion and financial sustainability, optimizing where they can. With online platforms and affordable services, there’s potential, but it often requires a strategic approach to manage costs effectively. This democratization comes with added responsibilities for artists as they navigate an evolving landscape, balancing creativity with cost management.

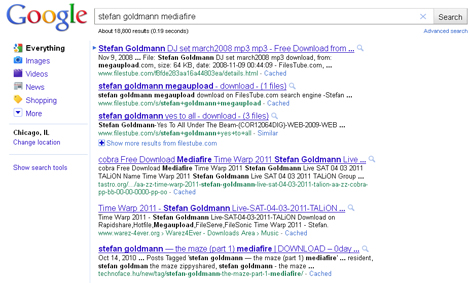

The world is at your fingertips

Others fell victim to it. Absurdly, the complete disappearance of economic barriers to distribution (offering a free download doesn’t cost more than the time to upload the file) hit the wallets of the “indies” first, stripping a substantial part of their income. This mostly affected the artists and the personnel around them: designers, engineers, studio musicians, promotion and label professionals, music journalists, et al. The mass of competition they encountered meant anyone with a limited marketing budget had a difficult time surviving in the market. With the same promotional tools available to almost anyone, they lost their efficiency. The professionals listed above basically lost their income. In 2000, an average vinyl single generated a return of a couple of thousand Euros, while in 2011 the same single generates a loss of a couple of hundred Euros, even without what were formerly known as “production costs.” Anything on top, like a bigger production, a decent mastering, or proper sleeve design became factors of deepening material loss. That area of the craft gets subsequently cut off and replaced by an undiscriminating routine of two-step-distribution: “save as” and “upload to.”

Fleeing to a purely digital distribution doesn’t look that much better in general: only an established artist backed by a strong physical release experiences significant digital sales. The overwhelming majority goes by unnoticed. The average “digital only” dance single generates around 100 Euros of profit, for both artist and label, now most often being the same person. And these figures go down, too. Today a couple millions artists try to reach a few hundred people. Or like the contemporary pun puts it, “In the future everyone will be world-famous for 15 people.”

Vinyl pressing plant from the days of yore

The result is a wide spread de-professionalization. If an artist regularly loses money on her efforts, she faces an economic end to her endeavors sooner or later. Being a “musician” is increasingly becoming a profession for those coming from inherited wealth or being mercantily exceptionally clever. It’s less then ever a question of the intrinsic quality of the music. What used to be done by professional enthusiasts now becomes the domain of the artists — turning them into designer, PR dude and distributor. It all subtracts from the time spent actually creating music. This puts additional pressure on the remaining professional environment. Nowadays it is increasingly harder to get hold of well executed services. Mastering, manufacturing vinyl, music PR — no one qualified enough is willing to tolerate the miserable working conditions and hilarious paychecks of these jobs for an extended time. Whoever has the chance seems to flee the music industry for something more prosperous. The error rate in manufacturing and distribution grows exponentially and actually feeds the market with ever shabbier products in content and execution.

Good luck learning to use one of these while holding a day job

There’s this die-hard belief that income, at least for the musicians (but not for the professional environment), will come from the fees for live performances instead. But how do you get live performances in the first place? Well, purchasing views and press recognition helps. The problem encountered there is that the media has adapted to the state of the music industry. In electronic music that means whoever succeeds in producing two singles may find himself covered by all relevant press and booked throughout the club circuit, just to be replaced by the next “lucky fool” (a term from stock speculation) about three months later. New artists get “pumped and dumped.” What about a year old break, a production that takes longer, or time for having a baby? Two weeks without a release are perceived as a career flaw for those who had their breakthrough in the last three years. A longer shelf life in the media and on the circuit seems to be granted only to artists who started before the big flood came, which is pre-2005 approximately (if I were to spend a year on the beach, most likely I’ll be able to continue exactly where I had stopped). Or to those who buy their coverage — although that only works over a longer period of time on a five-figure budget. Most others face the high probability of approaching music as something you do between college and some dull job.

The artists’ disillusionment leads to ever lamer results in music — why bother? A single produced hastily in two hours work sells 500 units, while a delicate masterwork moves 800 (plus a bit of beer money from Beatport). These figures are in constant decline, too. The market average first pressing of a vinyl 12″ is 300 units now, which regularly indicated sales below this figure (deduct records given away as “promotion” and to friends).

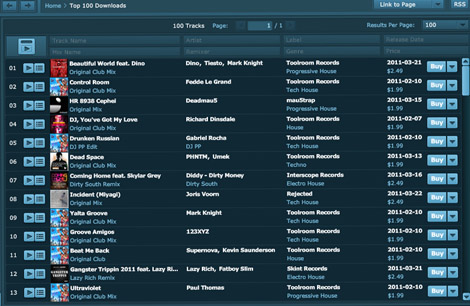

Beatport’s top 100 downloads

What have we learned here? The so called “democratization” didn’t work. Everyone did believe they gained access. This access by itself is stripped of value, though, because no one cares that DJ XY from Z has that new record out. Through any available channel I get dozens of requests per day to listen to somebody’s track. That’s after a spam filter and a disclaimer that I don’t want to receive files. The result is that I don’t listen to files at all — I do buy vinyl regularly. DJ XY doesn’t get the gig. If he does by accident, that’s for the cab fare. In Berlin, with its conspicuous population of 50,000 DJs, promoters and club owners don’t have to try hard. There’s always someone who will play for free if asked. Hey, that’s free promotion for the new DJ XY record. Meanwhile in the provincial town of Z, the locals “practice” for free, so they develop the skills they’ll need to “make it” in Berlin one day. That’s where things come full circle. No proper gigs, no record sales, no income. Anyone who is not already “there” doesn’t seem to arrive anymore.

The propaganda that the future will have us all giving away music for free in order to make a living on gigs has been proven wrong by reality. Because basically everybody does exactly this and still doesn’t get booked all over (or not often enough, as with most “mid career” artists). The exception being Radiohead, of course, but only after a decade on the million-dollar budget of a major. The only profiteers here (and biggest fans of piracy and Creative Commons) are the stock holders of the Nasdaq 100. If you want to make a living on music, buy the relevant stock and live off the dividends. That’s where all the money goes that used to pay musicians and music professionals some time ago. It says a lot about the other side of “democratization,” too: the individual in search for music experiences no upside. He pays for the returns of Apple, Google, Beatport and the speaker fees of Larry Lessig and Chris Anderson by being lost in a flood of irrelevant, crappy music and the feeling that others had more fun before (hence the retro obsession in today’s music). The total de-motivation doesn’t manifest itself only in the musicians’ under achievements, but also in the annoyance of everybody else. A frustrated DJ plays lame tunes in front of people bored to tears. That’s the average event out there. Alternatively, a collective nostalgia for some era of “old days” prevails. Everyone keeps doing the same thing out of the fear that the slightest deviation from the norm will scare away the small remaining, yet patient audience who goes along because of a lack of alternatives (we dance either because we paid or because the drugs kicked in).

Nasdaq studio

Did that depress you? Now, here comes the good news: exactly because everyone seemingly performs to the lowest still acceptable standards, all you have to do as an artist is to unleash disproportional waves of creativity. Since nothing promises secure success anymore, all considerations to what “works in the marketplace” can be freely dumped and forgotten. The more out there you get, the better. It’s the only way to stand out in a totally dull environment. The advantage is, put cynically, that the old channels are jammed. Whoever tries to break through them following “proven” old ways (which usually means emulating other people’s career paths) is wasting time and energy. We can’t learn much from studying the careers of Carl Craig or Ricardo Villalobos anymore because the conditions that enabled them don’t exist any more. The channels that do work are found elsewhere and are open to those who possess endurance, individuality and substance — the values that are disappearing most rapidly now.

To an extreme extent, success in the arts is subject to random factors (we see many successful people who have no clue how they got there, how to stay there or how to repeat it). The more radically and frequently you stand out, the more often you get exposure to those factors, thus increasing the probability of channels opening up for you. That is not spamming the Internet but creating radically individual great music in the first place. Once you enter the channel, you allow more factors to work for you, since these tend to add up (path dependency). Art always had to be great (whatever that is) and move people in order to succeed, too. But now there’s that third dimension of having to create a wide gap between you and the competition, even if that’s just within one genre. If you can implement this idea in your work, the flood is not threatening at all anymore since it works against itself. “Unique” is the most valuable word in a crowded environment of generic ideas and overwhelming redundancy. Striving for this quality is also exactly what is most rewarding artistically. Besides screaming fans and free drinks, that is.

What the music buying experience used to look like

A very odd example for creating stand out events: I had that funny experience when I recorded an album for cassette last year. No one involved expected anything more than to have some fun with it. Still, I spent a lot of effort on this one, specifically on getting my head around the question why to use a cassette at all. No one else would have put more work than necessary into such an obsolete format. And just that brought in a lot of attention, which any file on Beatport, regardless how good it is, wouldn’t have done at all. And there was no free lunch involved. On the contrary, distribution was severely cut down to a very few sources. Today it’s actually so much easier again as long as you can get your head around the notion that “anything popular is wrong.” Especially in mainstream media like Germany’s Der Spiegel or UK’s BBC (in features, not the usual playlists), I’ve only been covered because of totally odd projects. For the same reason new opportunities follow, which artists who cling to functionality and marketplace consensus never encounter. I don’t play techno clubs exclusively now, but also find myself scoring a ballet, performing in museums or getting calls from classical performers for collaboration — my techno background makes me stand out in these settings as well. In return, crossover encounters of this kind add that edge to the artist’s profile which feeds back into the club scene. It’s definitely more rewarding than spamming the internet with “listen to this track” emails.

Highly individualized, lightly advertised work is way more attractive nowadays than consensus-style work, advertised to death (short, unsustainable hype is the most one can hope for there). People are starting to realize this. Many top labels stopped promoting their new singles for instance. It just appears in the shops and that’s it. It’s not unlikely that artists will increasingly lose their interest in having their output available all over and seek for a more intimate exchange with the audience. Why plaster the Internet with files? Who finds that valuable anymore? Imagine an incredible piece of music available only once — on dubplate. Or let’s consider falling back in history — music only in the presence of its creator. No release. Come to the concert. Enthusiasm will be back when you get this feeling of attending something really special. How to create this feeling for the audience is the core task of the creatives, if they deserve that name.

—————————-

Postscript:

That said, it still takes a huge amount of time and dedication for an artist to develop a standout profile. This raises the issue of financing a career in music. Since the indies mostly lost their capacity to fund musicians, the artist’s required initial investment has become higher again. Usually people argue there will have to be some sort of day job then. As aforementioned, that would be perfectly fine if being occupied all day with something not relevant to music didn’t actively hinder you from devoting yourself to developing your artistic edge. Your mind will be occupied with other stuff instead of exploring the areas of sound where it gets deep. To be able to create stuff that outlasts two weeks, you’ll need to go full time at some point.

Even after tolerable initial periods of day job-cross-finance, those who succeed are never safe. Since the available funds (those remaining after the Nasdaqs sucked out what they could) get distributed to more and more people, even electronic music’s top and near-top level artists’ income drops rapidly. Periods of sufficient remuneration are followed by periods of economic frustration. Therefore there is a need to have sources of income that are independent from your own music’s direct returns. That is, any income that can be obtained with spending very little time on it — no day jobs allowed unless you are a grossly overpaid consultant for a few hours a month, like I am occasionally. One may consider the pros and cons (there are such) of grants and fellowships, commissions from the industry or institutions, as well as sources of passive income. The latter means that once set up, a scheme generates income without investing further time — interest, the concepts of arbitrage and leverage, or exploiting details of copyright law may serve as rather abstract examples here. How to make them work for you would be a topic of it’s own. Separating income and music in your head can be deeply rewarding. The freedom experienced in creating music to your own criteria first and even “against the market” if necessary is way more elegant than trying to squeeze as much as possible out of music that has to produce your paycheck. That is another factor contributing to an artist’s longevity in the market — having guts and principles. Get your head around it, do your homework and you’ll quickly see solutions that work for you.

Stefan Goldmann is an electronic music artist, DJ and owner of the Macro label. This article, which first ran in Silo magazine, is translated from the German.

[…] наоколо, както Ñам обÑÑнÑва в един забележителен текÑÑ‚ от 2011, каÑаещ уÑпеха в електронната музика въпреки […]

[…] it in Electronic Music, despite democratization,†Bulgarian-German DJ Stefan Goldmann admits that electronic artists have a harder time establishing themselves because of two factors: “lowered barriers to participate,†or simply the ease of software and […]