In “Everything Popular Is Wrong,” Stefan Goldmann claimed that the more artists deviate from the known and established, the better their chances are for success. But why should this be so? Now he offers a detailed examination of the psychosocial framework that underlies what we listen to, looking into the factors that decide what is culturally relevant and what is not — with surprising results: exploring the unknown is not only more fun, but also more rewarding. You can read Part 1 here.

Life cycle: crystallizing fields and the avant-garde

For an obscure speech, held in 1961 in the German city of Lübeck, anthropologist Arnold Gehlen designed one of the most accurate descriptions of how culture works in the big picture. If there ever was a valid explanation of how cultural styles emerge, grow and die, that’s the one. Let’s have a look:

He called the concept “crystallization”[1]: any new, emerging field of culture grows to the point where its boundaries, basic rules and antitheses are found. Once these are accepted, the field “crystallizes,” which means it doesn’t grow further beyond but develops ever smaller subdivisions and variations within ever smaller categories. Novelty and some surprises still occur regularly, but the field’s boundaries are not crossed and the basic rules don’t get violated anymore. Basically any metacategory of 20th century music of the western world seems to have reached the stage of crystallization, be it jazz, rock, contemporary classical or techno. Since all big subcategories within these have been discovered and occupied a long time ago, we now have shallow novelty of the kind of disco edits or “slowhouse.” When there is no clear path ahead, moving back and searching for the overlooked crumbs is just as good an option (in the earlier stages no one bothers looking back). Becoming aware of crystallization effects is the reason why we feel there was greater music being created in the past. When a new cultural field opens up, exciting new categories emerge and those discovering and promoting them have a far greater time at it than later explorers of the field.

Along these lines we can also define a widespread term: Those pathfinders traveling virgin roads are described as the “avant-garde.” In the language of the military, avant-garde used to refer to those troops of the cavalry who went into the battle first. In the arts, avant-garde means nothing but identifying a new category and occupying the lead position in it. Then it is all about waiting for the flood to set in. It is the only definition I can think of that makes sense in conjunction with the military meaning of the term. It is not about making weird sounds and shocking the public as often assumed. Once something has been established, it doesn’t make much sense to label mimicking or preserving efforts avant-garde anymore. The association of avant-garde with earpain is grounded in a different observation: every truly new aesthetic seems alien and unpleasant at first. Only later we learn to process it and enjoy its characteristic features.[2] That usually happens when more artists enter the scene. When no one follows the avant-gardist, things stay alien.

Extended cycles: museum categories

Categories emerge, grow and eventually fade away. So do the careers of their inhabitants. When no one is interested in one category, leadership doesn’t mean much. Even most successful styles and fashions in music disappear sooner or later. Those categories that survive along their representatives often exist for the lifespan of the fans that spent the time to learn the category’s cultural codes. You know those concerts where everyone is 60+. Some categories are so strong that they live on for centuries, if not almost infinitely. Probably ever since someone beat a stick on a stone for the first time there has been some equivalent to the 4/4 beat we call techno today.

Every generation rediscovers the category and feeds it with its own stars. This is most obvious with classical music where every few decades there is the new superstar soprano, conductor or violin virtuoso. It is also a “museum category” preserving the live performances of works written sometimes centuries ago (a recording is still a poor substitute for an acoustic live performance). So does every new generation form its own rock superstar and a lot of electronic music seems to enter a similar road. In a crystallized environment eventually a prototypical subcategory is deemed worth to become a museum category. Then there come musicians who want to sound like the prototype from back in 1715, 1923 or 1988.

Case study: Minus vs. Richie Hawtin

Let’s examine the story of the Minus label. When Richie Hawtin founded it as an outlet for his own productions, he already was the main exponent of minimal techno with a string of hit singles and extremely refined albums under the moniker of Plastikman (most notably Sheet One, Concept 1 and Consumed). The Plastikman project was so influential and successful that people had its logo tattooed. When he opened Minus up to other artists, two things had happened: The first wave of minimal was over, leaving basically only Hawtin and Basic Channel as still widely reknowned artists. And Hawtin had almost stopped releasing new original material (except for the artsy album Closer and two mix CDs). Minus formed a crew around Magda and Troy Pierce, and facilitated associates like Marco Carola and Mathew Jonson. A second wave of minimal techno swept the world, much bigger than the first one and went on to dominate dance music almost to a degree only trance had reached before. The Minus crew was probably at the top of it, accompanied by the likes of Ricardo Villalobos, Luciano and many others. Intriguingly Richie Hawtin, who hadn’t released one track contributing to the renewed minimal style, peaked his career in terms of reach and reaped rewards, becoming techno’s number one DJ. Compared to stadium rock, minimal techno is still a miniscule niche market. Yet its leading artist mentioned in a recent interview that he sometimes plays up to three performances a night, often in different countries, which is only made possible by employing the services of a private jet.

It is a wonderful example of how categories develop. After helping to form a first minimal subcategory of techno, Hawtin was recognized as its leader. Branding the Minus label and opening it up to others, their efforts accelerated his position as the one “owning” the style in the minds of the audience. With thousands of enthusiasts and artists jumping on the bandwagon and deepening the category to gargantuan proportions, Hawtin got leveraged proportionally to the size of the category itself. Once it outgrew the other subcategories of techno, he automatically became the leading artist of “all techno,” although the thousands of tracks that actually formed and defined the second wave of minimal were all produced by others. The critical point was making the transition of personal “first call” status from old minimal to new minimal. As we see, this can be achieved even without actually producing any new music in the style in question. This is not to be misinterpreted as unjust recognition though. Hawtin had shifted away from primary production to pushing new means of production, presentation and distribution. He spearheaded promoting a whole industry from Native Instruments to Ableton to Beatport, shaping the infrastructure of new minimal and beyond like no other artist. He’s also a really nice guy.

The gap between the category leader and the next on the ladder might be so wide that it even tolerates severe flaws in the primary sector: you might get away with continuously unexciting or even bad performances. In several interviews Hawtin cultivated an attitude of method over content, claiming he doesn’t even listen to the tracks anymore before he plays them and instantly forgets about them afterwards. I listened to a three hours set of his recently and indeed it seemed like watching a factory production line rather than a performance of music. It’s alienating and amazing at the same time, truly avant-garde in its dedication to taking things to the extreme. A new arte povera (a 60s Italian movement of making art from trash materials) seemed to have formed. As you see, at the end of the case study we are not with the label anymore, but with its leading artist. That’s what category leadership does.

The artist: category elasticity and time factors

Most great categories are discovered rather quickly by those who manage to move in boldly without giving it too much second thought. Whatever is possible will eventually be done. That is also why the audience doesn’t grant artists too much time to prove their talent. For visual arts, Chris Dercon, head of Munich’s Haus der Kunst museum, once estimated an artist has about seven years to break through[3]. In music it might be less. Especially after you have some initial success there will be limited time for your full “potential” to unfold. Slow growth is a concept punished severely by the social environment. If people come to your concert in order to find a half empty room or you deliver a poor performance, they are unlikely to try again unless they have some very good reason to believe next time will be dramatically different. If you already spent a couple of years on the circuit that’s an unlikely scenario. Also the media and promoters will think you aren’t “hot” anymore if you don’t deliver accelerating results early enough. That is also why a cover story or other overblown exposure too early in an artist’s career might bring things to an early end: rewards associated with fully shown potential require just that. It is of benefit to an artist’s development if rewards and recognition lag slightly behind her actual level.

Then also once you have your name associated with a category, it is extremely hard if not impossible to move on to a different category. Once people know you as a black metal goddess, you won’t seem credible in pumping out dubstep tunes. It is actually easier to change when you are below superstar status. The only super-prominent historic counterexample that comes to mind is Miles Davis, who changed over the whole jazz world every couple of years throughout a career that lasted half a century: Birth of the Cool, Kind of Blue, Bitches Brew, On the Corner and Decoy are just a few examples, all differing wildly from each other. Yet they include some of jazz’s biggest (including the biggest) commercial successes ever plus separately inspiring thousands of musicians to follow and deepen the styles Davis designed. Although he regularly alienated his fans, he also managed to build up new followings every time change stroke. If the fans stay, it usually indicates that you didn’t leave your category.

On a side note, superstars also regularly fail to take into account that they are such only within one category at a time. Jeff Mills and Ellen Allien are still all over as DJs, but their fashion lines never went anywhere for instance. Miles Davis’ appearance in “Miami Vice” didn’t quite make him a Hollywood celebrity and his much advertised late paintings haven’t make it into the MoMA so far, too. The ultimate fallacy is when established artists try to reposition themselves by reacting to new developments imposed by others: they regularly fall to the bottom. When wild pitch pioneer DJ Pierre started to play the post-minimal hits of the day, it was the last time we heard of him. Unless you have pioneered the new thing, you’d better ignore it entirely.

Do we still need marketing?

Don’t expect a description of how hits are crafted or what kind of supportive promotional efforts are necessary for an artist to actually get his categorical findings into the minds of the audience. That’s a slightly different thing that’s too deep to discuss here. Yet the relation between category leadership and marketing efforts should be clear: no marketing effort will get an obvious “me too” artist’s profile sufficiently off the ground (this is the one point 100% of music marketing books fail to discuss). Within the range of the possible, the avant-gardist of a new category will have the biggest chances to be considered the best and therefore will be the easiest to promote. All categories are not created equal though. Some will have bigger potential than others, since they will address a need that is culturally relevant to more people. That’s usually where trial and error begins and predictions fail. Categories compete, too. The bigger the gap between them the smaller become the competitive effects. An isolated, small category might have bigger problems initially communicating the means necessary for understanding and enjoying it. So the initial promotional effort will have to be bigger. Once it is established though it will be more stable because fewer other categories will overlap with its position. Vice versa, a new category closer to existing ones is easier understood, but also more threatened by competition. It is quicker to establish and quicker to be forgotten. Closeness to the known is the prerequisite for hyped fads. That’s why we regularly encounter two word style names that start on “new” (or “nu,” for that matter).

Of course, marketing allows for some severe distortions, too. The most notorious is known as “payola,” referring to purchased exposure. In its contemporary form, usually ad money leads to overexposure of certain artists (attention they wouldn’t get without money being exchanged). When a song is on rotation on the radio it must be popular, social proof teaches us. Even in cases in which the connection is obvious we seem to assume that if an artist is willing to invest more than others there must be a reason (i.e. his talent justifies the investment)[4]. And we move along too often. I know of concert promoters who booked artists on the basis of the number of “fans” on their social networks, even when they did know those numbers were manipulated by a piece of software adding random people.

Randomness and self-regulation

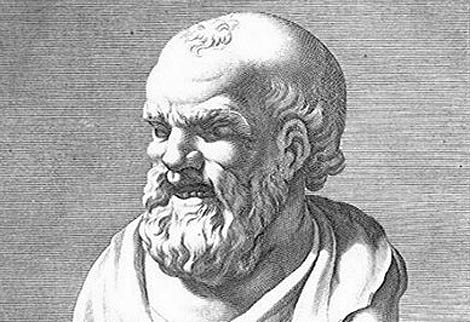

Ancient Greek philosopher Democritus (circa 460–379 BC) used to define “chance” as the ignorance of the hidden cause of an event[5]. Often we attribute some unexpected outcome to random factors, since we don’t see any pattern that would allow us to explain what happened. The arts seem to be a field whose dynamics we regularly fail to understand, which results in a constant stream of surprising events. The very nature of competing categories means the other rules are constantly changing, making exact predictions regularly sound idiotic. One would wish to have clarity at least that the arts are a contest of ideas and the bolder new idea shall win. In reality, crossfire comes from even more factors than just marketing abilities. Someone figured out that pianists competing at a piano competition regularly had greater career chances if they played later than others. Juries happen to be in a better mood in the afternoon. Years later those who played in the afternoons had more concerts and better recording deals[6]. It is impossible to identify all such biases. When you hear someone lamenting that “the time wasn’t right,” he might be referring to this complexity of the unknown. The deep insecurities of which outcomes to expect actually promote diversified culture. Many attempts that turn out to have no chance to succeed nevertheless do get initial support (“trial and error”). A lot of category depth has been gained by the belief that what worked once might work twice. And a new category’s reach won’t be obvious before it has been actually built and tried.

Yet the concept of category leadership by definition works for a minority only. When it seems to install the same hierarchical structure in any new category, this is only true as long as the majority wastes its time chasing categories that already exist. Innovation seems possible because we clearly know what the mainstreams are. If every artist would first and utmost try to differentiate from all others, we would face a self-regulating process. If the mainstream gets fragmented new rules will emerge, requiring new approaches.

The garden of the closing paths

If the above descriptions hold some truth, it is not the most hostile environment to be in. Most musicians have marveled over which marketing strategy would help them and how to adapt their sound to fit “the market” — just to wonder why what worked for someone else simply doesn’t work out for them (exactly because it worked for someone else). In the light of the mechanics of category leadership such considerations seem plainly wrong. The need to differentiate from the established encourages experimentalism and individuality — not the worst things around. On a sad note, going deeper in an established category is not rewarded. For the cultural (and economic) success of any piece or style of music quality is overrated. Eminence is gained because of the potential for social distinction. Any social group within a new generation builds its identity to differ not only from previous generations, but also from its social peer groups. That’s why it will embrace anything that seems new and different, no matter how stupidly new or different that might be. Listening to a “better” song never did the job, exactly because it lacks the effect of clear cut social distinctiveness.

Our culture is not so much cluttered with successful bullshit because we have no taste, but because our brains are built to pay more attention to novelty of form than to variety within a form. The stone age application: your chances of survival increase when you recognize clearly unfamiliar patterns rather than variations of familiar patterns. It’s some kind of deer, so eat it. But beware of that new snake, insect or other tribe with unclear intentions. Quality helps only later on to sustain the life of a category (not necessarily the life of the one who delivers it). Once we grow aware we’ve been listening to trash, we eventually move on and the category fades. On the other hand our culture is cluttered with unsuccessful bullshit, too, because we simply don’t learn about how our minds function. It is a default on the side of the musicians, concert promoters, labels and distributors of culture, deeply misunderstanding the audience. Instead of pursuing individualism, they keep searching for repeatable formulas. As the joke goes, “I don’t understand why nobody is interested in my music. It sounds exactly like anybody else’s.” Ironically, what is called “commercialism” regularly fails in the market at an astonishingly high rate.

Once we learn the aesthetics of one category, we stick with it. People are very loyal in their tastes of music. We only change our preferences on flat fads and fashions. Search and learning “costs” are too high to change complex, deeply built tastes regularly. That’s why our parents still enjoy the same music they enjoyed when they were twenty (“gerontorave” becomes a less futuristic outlook every day). This encourages artists to build categories aesthetically as deep and strong as possible in order to engage their audience “for life.”

Stefan Goldmann is an electronic music artist, DJ and owner of the Macro label.

Footnotes:

[1] Gehlen, Arnold: Ãœber kulturelle Kristallisation. In: Anthropologie und Soziologie (1963): pp.311-328.

[2] Berlyne, David: Aesthetics and Psychobiology. New York (1971): p.193.

[3] Dercon, Chris: Wir sind eine Marke. Interview, in: Sueddeutsche Zeitung (10.5.2006).

[4] Compare Frank, Robert H. / Cook, Philip J.: The Winner-Take-All Society, New York (1995): p.192.

[5] Quoted in Bennett, Deborah J.: Randomness (1998): p.84.

[6] Ginsburgh, Victor/van Ours, Jan: Expert Opinion and Compensation: Evidence from a Musical Competition, in: American Economic Review 93 (2003), pp.289-298.

This article seems to come at just the right time for me.

I feel like I’m approaching a plateau of sorts, where instead of trying to be “unique in my field”, I just want to make my own field. Not that I plan on revolutionizing music as we know it, but that I want to break beyond the barriers of the music I feel like I’m “SUPPOSED” to be making, and just go make my music.

I read a comment by another reader in your “Everything Popular is Wrong” article that stated, “We are the first generation to truly span the analog/digital divide in just about every electronic and interactive aspect of our lives… we recognize and respect analog, but embrace the convenience and “democratization” of digital (…) but we did not consider endgame, and here we are, slaves to our own dreams and ideas.” While this is referring to a specific aspect of the industry, it is pretty telling as far as having a short-sighted outlook on our own art.

Reading this article (as well as part 1) is helping give me the push I need to just start making music that I feel rather than trying to fit it into some sort of consumable box. Sometimes you just feel like making your own damn box. Much appreciate the time and effort you put into this article.

Regards,

David

http://www.soundcloud.com/the-snark

http://www.facebook.com/TheSnarkMusic

Probably one of the better researched and informative articles relating to music and society that I have ever read. Thank you for your effort, Stefan.

Informative, well researched and invaluable. Thank you.

Great article. Possibly my favorite yet. Serious food for thought.

normally don’t make website comments, but i’m trying to procrastinate like never before.

so, i’m glad someone is writing and publishing thoughtful articles. there are lots of interesting ideas here, but i feel both parts 1 & 2 start strong and then drift. at the end, conclusions get replaced with extraneous assertions. maybe they’re just ideas: rhetorical flourishes. but they distracted me, and made me suspicious of the overall reasoning. examples:

“The stone age application: your chances of survival increase when you recognize clearly unfamiliar patterns than variations of familiar patterns. It’s some kind of deer, so eat it. But beware of that new snake, insect or other tribe with unclear intentions.”

i’d challenge that. stone age hunting–as practiced by the bushmen of the kalahari–is based on pattern recognition: examining a lot of sensory information and improvising the hunt based on variations of a large body of knowledge. said hunters can identify hundreds of animals just by the smells and tracks they leave and variation on those patterns including whether the prey is: moving fast, wounded, sick, etc. also, a byproduct of human’s unique facial recognition capabilities and social dexterity among animals, is our brain “seeing” faces, recognizing facial patterns where there are none, like jesus on toast or a face in the dark. or we recognize a stranger as a friend at a quick glance from far away. the brain actively fills in familiar information where it doesn’t exist. thought to be evolutionary based on watching for predators. no specific citations, but some of it comes from david linden (john hopkins professor of neuroscience) “the accidental mind”.

“Once we learn the aesthetics of one category, we stick with it. People are very loyal in their tastes of music. We only change our preferences on flat fads and fashions. Search and learning “costs†are too high to change complex, deeply built tastes regularly. That’s why our parents still enjoy the same music they enjoyed when they were twenty (“gerontorave†becomes a less futuristic outlook every day). ”

recent neurological work suggest the reason people stick with music from their youth–and the reason for its great emotional appeal–is due to the particular nature of adolescent brain development. from “this is your brain on music”

maybe i’m just too easily distracted. but i wouldn’t comment if i didn’t think the vonnegut, crystallization of culture, and other parts were compelling. i just think the article could be clearer with more editing. at the very least to prevent online reading fatigue (though great for procrastinating) 😀

Brilliant article.

small edit:

“miles davis… career lasted half a decade” – er half a century right?!

@Chris: pattern recognition is a truly fascinating phenomenon. but viewing the world in patterns is exactly what i mean here: grouping information on the base of familiarity is a reduction of complexity, casting out redundance. in the hunter example, it is this reduction towards a pattern that allows to recognize an animal through its trace. or someone’s music as a “me too”-product (as opposed to: “wow, this is different”). when you can’t put something you see in the established patterns, the alarms go on. there is more “processing effort” to deal with the unfamiliar.

as for brain development and tastes, “search costs” is a broader explanation of the empirical phenomenon. if it is actually possible to change after a certain age or if it would be just too much effort doesn’t matter much – since the result is the same.

@daniel: oops. that’s correct!

Fantastic article- keep em coming… I kind of used this as an excuse to put down some thoughts I’ve had about this. Apologies for some generalizing- always exceptions always exceptions…

A few thoughts, provocations, disagreements and a question:

Why use the word category instead of (micro)-genre?

I’m a little bit terrified by this push towards “new categories” as a way to stand out in the crowd– to clarify, I’ve been having a number of discussions lately concerning, to summarize, a pervading feeling among friends and colleagues that the future has somehow become an old fashioned idea. The very notion of the radically “new” seems nigh impossible in the face of the temporal and geographical folding that the internet enables (+) and imposes (-). A critical imagination of the possible that isn’t directly attached to tangible, immediately accessible examples of the expanded canon often occurs to me as a prerequisite for any genuine innovation. The encapsulation of every single variation on a theme into critical micro-genres–ossifying the production/compositional strategies before they can “go deeper”–seems to pre-render our generative capacity towards a type of strategic grafting or juxtaposition instead of the development and progression of creative ideas. Furthermore, all larger, commercial modes of presentation (club or concert-hall or CD etc.) carry with them specific economic and social demands that the music they support is expected to support in turn. Within this system, new “categories” are therefore often novelty on top of formula (fads)–the emphasis and repetition of a few new tricks that the same old dog learned. Novelty wears off quickly and by its very nature cannot be the basis of an “aesthetically… deep and strong as possible [category]”. It order for it to function in the market commercially it generally needs to be heavily supported by a specific accompanying aesthetic and critical support, the latter of which has its own motivations and ambitions that the music is often expected to be in sync with as far as I can tell. Anything that really would be truly new, would not be easily situated within this state of things, where commercially viable music has been relegated to a soundtrack for consumption.

At a semi-forward thinking thing at a club, after about 2 minutes I heard “I can’t listen to this shit, let’s go to the other room, they are playing houseâ€. After 15 the dance floor was halved.

Western classical music, on the other hand, developed slowly over the course of 300 years (if we start with the baroque and end with cage, the cul-de-sac of serialism and the rise of popular culture) through a constant process of “going deeper”, finding the spaces rhythmically and harmonically that could still be filled in and employing them to specific conceptualized effect. Of course, now this history is a world-heritage mausoleum, and offers little advice to the submerged creatives among us. Still, species counterpoint can be seen as a parallel to one of these “techno production secrets” 101 tutorials, a standard boring starting point, but with a massive space to develop into, once the rules are accepted as more fluid.

Creating new genres just seems a bit like creating new ghettos as supposed to participating, promoting and generating a truly pluralistic, advanced and progressive center—ground zero here being, as regards electronic dance music, what get’s played in the clubs. That people shouldn’t waste their time mimicking exactly what’s already been done goes without saying–though this new culture of production courses, mass music technology that makes getting standardized results easy as pie encourages otherwise, precisely because the new market for production isn’t in you making money off your creativity, it’s other people making money off of your desire to be creative (your last article). Unfortunately, and a point that I think your article doesn’t engage with, the avant-garde rarely gained inroads by coming out immediately with something new—the ability to experiment outside of the periphery was built upon previous commercial successes in most all of the cases I can think of. I know observations as supposed to prescriptions are being offered here, but maybe it would be better not to dismiss quality as a requisite for initial entry, as you polemically suggest, and offer, instead of “categoryâ€, a persistently progressing catalogue of works as something that might be rewarded and recognized? I guess that doesn’t address short-term emergence or eminence, and perhaps has slightly more realistic expectations of our capacity to produce and absorb originality, but I still think that that’s a good recipe for long term success…

I just wanted to add that it’s actually the responsibility of the clubs and the tastemakers to develop strategies to bring these types of new production in and to say, directly, “this is is what we are looking for this is a way for our program to develop and evolve beyond the basic styles we are known for.” An open call for stylistically-different, new works for a Berghain event series. Not just something for the big guys to be more experimental in, but also a chance for the little guys without the contacts, trying to claw up, who are utilizing other strategies, to get some real exposure and institutional support for their art. That would be a really great accompaniment to the elektroakoustische salon strategy. A way to open a few pathways for unsigned, self-produced, unsupported music to get into the halls and ears.

“Not just something for the big guys to be more experimental in, but also a chance for the little guys without the contacts, trying to claw up, who are utilizing other strategies, to get some real exposure and institutional support for their art.”

@fman I’m with you here but unfortunately I see a degree of exclusivism /protectionism in every scene, maybe because things are so competitive and there isn’t much of a cookie to go around..not that many opportunities.. Always been a part of how the music biz works.. hope I’m wrong ha!

Is Mr Goldmann being paid for these articles? Because he should be – these are some of the more fascinating, coherent and insightful pieces on music I’ve read in a long while. Thank you to LWE for publishing these and bringing them to a wider audience as well.

After I commented on the clarity of the first article, I’m really struggling to follow the meaning of this sentence:

“your chances of survival increase when you recognize clearly unfamiliar patterns than variations of familiar patterns.”

How do you recognise something that is clearly unfamiliar? If it was slightly unfamiliar then maybe, but ‘clearly unfamiliar’ implies 100% unfamiliar, ie cannot, by definition be recognised.

Hey Mark, I think there’s a “rather” missing from that sentence. “your chances of survival increase when you recognize clearly unfamiliar patterns rather than variations of familiar patterns.†Not sure if that helps, but it at least reads correctly now.

lovely writing, keep em coming like this!

Fascinating article. Top work Stefan on figuring out and succinctly getting across those views.

As dubstep and the like expands with the current youth generation it is going to be interesting how house music and techno develop. Or if they stay the same with an advance to stadium proportions like rolling stones?. In fact I guess SHM and Guetta are already doing that…

just remembered this from ctm 2007 and thought it was somehow relevant:

http://www.janrohlf.net/works/genretapete.html

Re: “familiarity”: as in the pattern recognition example brought in by Chris Widman (see above), familiar information is recognized as such. In our natural environments information usually is never exactly the same (hence, it should be always new) – but our brains split it into two: “core” information and redundancy. If the core features match, i.e. patterns are recognized, it can be considered familiar and processed “as always”. Anything else is ignored (redundancy). If there’s a core mismatch, we recognize this. Then the quest for appropriate reactions starts, eventually building new patterns to recognize in the future. That’s the “shock value” of the new, and we do sense this.

When you decide to jump out of an airplane with a parachute for the 1st time, you’ll very clearly sense this. After your 20th jump you’ll probably have very different feelings – and new routines. The New gives us the thrill of its encounter, while the familiar lets us put our senses on autopilot. Hope that helps clarifying the sentence!

I found this is a very interesting read with many worthwhile titbits. Although I do agree, that some clarity here and there could lift this to Wire-worthy material.

However, I am left with a want for a clear line to be drawn between popularity and quality. Despite the popularity of category leaders, and the way these distance themselves from others further down the ladder, you seem to be pay no attention to the qualitative aspects of the music.

This argument may be missing the point of your article, but it seems difficult to talk at such length about the emergence of genres and first-movers (leaders) without giving any thought to the importance of the quality of the product. You could argue that quality has little to do with chart-music. But when it comes to minor categories and sub-categories, we move into a territory where most followers are critical and choice-conscious. They did not become followers of these categories by coincidence, but through acquisition of knowledge of other categories. Through critical selection and by diving deeper into the murky waters of more general categories.

I hope it is clear what I am getting at here.

@Tobias: “you seem to be pay no attention to the qualitative aspects of the music.”

– quite to the contrary: I argue that quality is of not more than secondary relevance to the people who follow ANY genre / subcategory / branch of music (not just “charts” – the whole essay doesn’t deal with hits, but with categories). Don’t get me wrong – the idea of “quality” is very important to many creators, including myself, but that’s not how culture works socially. What one group of people rejects because of “low quality” is exactly the reason why another group of people jumps on it.

Hendrix was considered an inferior guitarist because of his distorted sound. As recently as in the year 2000 a reknown pop producer wondered why people would bother to listen to “demo-quality music” (i.e. electronic music). “Quality” is the hardest thing to define. What was quality in punk? Certainly not Steve-Vai-level performance skills. What was the quality of techno? George Massenburg-level engineering skills?

We have a definition problem here. Most commonly, quality probably means refinement, but it seems more that genre-building itself sets the standard of what becomes genre-specific “quality.” Connoiseurs then of course recognize further refinement in accordance to that definition – but this does not necessarily bother the category’s leaders and their followers (hence, “quality is overrated”).

I think you are right though that under a different definition quality is critical for the longevity of a category. “Quality” then means the capability of a genre’s features to hold the attention of its followers – to keep them excited over time. That’s the watershed between novelty and long-term cultural relevance.

Incredibly well written piece. More than Wire-worthy in my humble opinion, this is top quality information. Thanks Stefan!

just brilliant. stefan explains what we all know in a way subconsciously and what we are not able to explain.

he names it and points it out.

it helps so much thinking deeper and clearer.

thanks so much for sharing.

Having wasted 15min reading this terribly written ‘essay’, I have to waste a couple more to let you know I found that utterly daft, value laden & agenda driven drivel. I just don’t know where to start with the wtf moments. Everything written here is based on very particular assumptions and understandings of the world and why people produce and consume music. Who actually listens predominantly to the music they enjoyed when they were 20? I don’t & nor do my parents. My tastes are broad and range across ‘categories’ (music genres, right?). Many people who lap up novelty crap in some fields of cultural expression also enjoy a passionately deep understanding and appreciation of some others. I don’t even get what you’re trying to argue here – it just seems like a whole load of generalisation and pseudo-intellectualising to no end. I hope I’m not being too rude (I did just lose 15 min of my life reading this) – maybe I just didn’t get it.

@ Marko: That might be an explanation: “maybe I just didn’t get it”

What seems really interesting is the fact that this really makes people take sides. You can’t be lukewarm to it. Those who disliked the content also argue it is “terribly written”, while those who love it say “incredibly well written.” Are we really looking at two totally different groups of people or is language an obstacle in understanding the content?

Thanks so much for this. I will share this with my friends… oh wait… I should just write my own, but it has to be categorically different from yours. Got it.

Paul – brilliant!

Those who can’t think up the categorically different spread someone else’s stuff instead, whatever they do actually.

Its a sign of the times. An economically unstable world can either lead to a suppression of creative juices because you can’t afford do it or having nothing to lose will spur perhaps a huge ground swell for something fresh Perhaps Robert Glasper(http://www.jazzwax.com/2012/03/interview-robert-glasper-pt-2.html) in jazz BBNG (http://www.allaboutjazz.com/php/article.php?id=41758) in hip hop are flicking their BIC’s to a new light in music listnership.

bit rough to call out slow house! down tempo house isn’t necessarily gimmicky! its been jacked by edit heroes

I am not a producer, I am not a DJ. I don’t like labels but for the sake of it, lets say I am a connoisseur listener, I say this because after reading many of the articles Stefan wrote on here I am very relieved that I am part of a bigger community here.

A community that is asking questions about electronic music, specifically asking questions that point to a feeling that music is NOT evolving as it has in the past.

I would like to think it evolved because the producers all started off with what they could afford MIDI wise, Today you get everything in one package, the possibilities of what one can create by far out paces 95% of the people who will try and hone their craft on it when they dont quite have the knowledge of what that crafts entails.

Producing a mix live on the mix itself while it’s playing is quality that most likely wont be repeated as that type of producer is not playing music as much as creating it for that specific moment to be heard by his audience.

The delivery of “new and different” sounds are not in the hands of someone like Billy Nasty or Lee Burridge who delivers the music toaudience by producing it twice so to speak as they will play something that the audience will love despite not knowing what it is.

Beatport and internet distributions means any half baked attempt will have some unsuspecting person buying it and that perpetuates the cycle of quantity and less and less quality.

I am surprised that people are surprised when they hear tracks that sounds like some software just vomited some random code out , compressed it and saved it as an audio file. Yes, every “GAP” year student and his best mate is “producing music”.

Maybe I should be careful to criticise, potentially, the Richie Hawtin’s of the future . As careful as I am, The gap year student’s music is CRAP. The harmony and melody of the music is gone. Most of the music being uploaded from literally anywhere in the world is just “NOISY”.

Google: “Fidget Dance” – not entirely sure the about the music they now also term as

“Fidget House.” It seems to be a South African thing only. The you tube videos with these 18 year old’s fidgeting to this fidget house is quite disturbing…. Unfortunately one night we were in a club where the one dj in the line up brought his fidget house music and a group of fidgeters, what unfolded in front of us was jaw dropping.

All in all if fidgeting becomes tomorrow’s new fad I hope that one day the history of electronic dance music can translate to something like this

=========================

HISTORY OF ELECTRONIC DANCE MUSIC :

=========================

1974 – Here, play this Kraftwerk.

1977 – Kraftwerk is old! It’s Disco Time play ” I feel Love”

1987 -“I dont feel love”. Here take this ecstacy and dance to acid house

1998 – That acid house is poisen. Play some Trance.

2002 – Trance is for stupid people. Play Techno

2005 – Techno is too busy. Need Minimal

2010- Minimal is too simple. Lets Fidget

2015- Fidgeted to death. Here play some Kraftwerk.

What would the world be without a bunch of chin stroking pseudo intellectuals over analyzing everything and throwing generalizations about like it’s going out fashion?

What would the world be without random trolls incapable of offering specific criticisms/points of disagreement chiming in to let the world know how smug they are?

@littlewhiteearbuds Smug? Hahahaha that’s rich!

[…] didn’t change, but the metacategory (“techno”) found itself being transformed.Read Part 2 of “Quality Is Overrated: The Mechanics of Excellence In Music” hereStefan Goldmann is an electronic music artist, DJ and owner of the Macro label. […]

[…] part 1 — part 2 […]

[…] Quality Is Overrated Pt. 2 | Little White Earbuds – Nightly In “Everything Popular Is Wrong,†Stefan Goldmann claimed that the more artists deviate from the known and established, the better their chances are for success. But why should this be so? Now he offers a detailed examination of the psychosocial framework that underlies what we listen to, looking into the factors that decide what is culturally relevant and what is not — with surprising results: exploring the unknown is not only more fun, but also more rewarding. The amplified champions In Kurt Vonnegut’s novel <i>Bluebeard </i>, its protagonist Rabo Karabekian muses on the origin of special talents and the diminished opportunities in modern societies: “I think that could go back in time when people had to live in small groups of relatives – maybe fifty or hundred people at the most. […]

[…] Everything popular is wrong: Making it in electronic music, despite democratization Quality Is Overrated: The Mechanics of Excellence In Music Quality Is Overrated Pt. 2 […]

[…] is defined by experimentation. There’s a great pair of articles by Stefan Goldmann over at Little White Earbuds (ca 2011) where he talks about the accessibility of the modern market and how that means it’s […]